One of the classes I’m taking when the new semester begins is an advanced study called Comedy: Theory and Practice. I got the reading list in advance and picked up one of the required books over the weekend at Barnes & Noble. I have to admit I was a little surprised to see Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious by Sigmund Freud on my Comedy reading list. Not that I expected to spend the semester getting down with Mel Brooks movies, but one can hope.

I’m almost through the book and believe me, Freud was no Henny Youngman. Even though the iconic picture on the cover shows him in a mustache holding a cigar, there’s no mistaking him for Groucho. Not even Harpo’s brother could pull off a joke that ends with, “She could abschlagen nothing except her own water.” They must have been howling in the streets of Austria with that one. Even the hunchbacks. Forget the Jews. No, really, forget them. Two Jews met in the neighborhood of the bathhouse. “Have you taken a bath?” asked one of them. “What?” asked the other in return, “is there one missing?” You’re killing me Sig.

Knowing what’s funny is serious business, and who better to get to the bottom of it than the father of psychoanalysis. After all, no one can resist a guy who hypothesizes, “An examination of the determinants of laughing will perhaps lead us to a plainer idea of what happens when a joke affords assistance against suppression.” What, you want repression? Try this: “But if we are to judge by the impressions gained from non-tendentious jests, we cannot possibly think the amount of this pleasure great enough to attribute to it the strength to lift deeply-rooted inhibitions and repressions.” Don’t say later I never told you.

All jesting aside, Freud presents some gems of illumination that transcend time and place. And without even listening hard, you can hear Henny and Woody in the background. On the subject of returning an insult to someone of a higher class without getting hanged, Freud offers us this snappy repartee: A German royal was making a tour through his provinces and noticed a man in the crowd who bore a striking resemblance to his own exalted person. He beckoned to him and asked, “Was your mother at one time in service in the Palace?” “No, your Highness,” was the reply, “but my father was.”

In its simplest terms (a place Freud never goes) anecdotal humor needs three things: an incident, someone to tell about it, and a listener. The motive and manner can differ along with the content. In the following joke that the book uses to demonstrate a mixed-meaning play on words, it is the listener who appreciates the satirical irony, which in turn pleases the joke teller: A doctor, as he came away from a lady’s bedside, said to her husband with a shake of his head, “I don’t like her looks.” “I’ve not liked her looks for a long time,” the husband hastened to agree.

To further quote Freud, “In laughter, therefore, on our hypothesis, the conditions are present under which a sum of psychical energy which has hitherto been used for cathexis is allowed free discharge.” In other words, bring on Young Frankenstein. But first, as long as you’re listening, a priest and a rabbi walk into a bar. . .

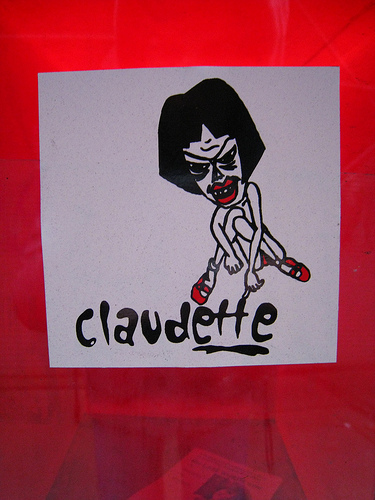

Daughter’s Featured Fotos examine Concepts And Sunsets